Almost three years has passed since SandForce introduced its SF2200 series of controllers. Despite well-publicised problems SandForce's SF2281, in particular, was a radical product; it was one of the first controllers employed by SSD manufacturers to push the SATA 6Gbps connection to its realistic limits.

Wind the clock forward to today and we are still seeing that same SATA connection getting use. And, surprise surprise, three years on it's enforcing quite the bottleneck to SSD speeds. Yes, controller optimisations and different flash configurations have allowed today's SSDs to outperform many of their predecessors, but the core, sequential speed aspect of their performance is still limited by the circa-560MB/s cap imposed by the SATA 6Gbps interface.

It is difficult to argue that an updated, faster SATA interface isn't well overdue. But with early information regarding Intel's 9-series chipset suggesting that SATA Express will not be provided natively by the upcoming PCHs, it could be left to board manufacturers to deploy a solution for SATA Express connectivity. That looks to be the realistic outcome for the near future, unless current information surrounding Intel's 9-series chipset proves to be wrong, of course.

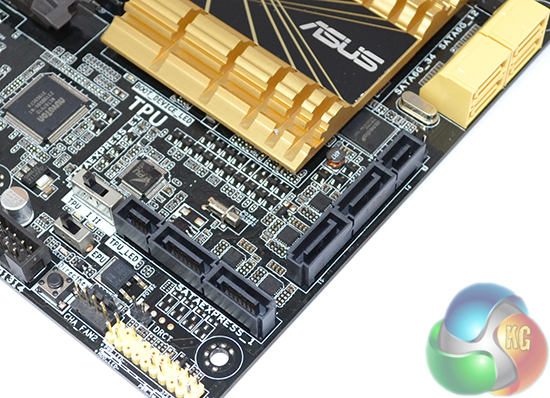

Cue Asus's take on the high-speed SATA Express interface, deployed on an adapted version of the company's Z87 Deluxe motherboard. Made possible by employing a purpose-built SATA Express controller from ASMedia and by re-routing a number of PCIe connections, Asus's design could act as an early representation of solutions to come.

We will analyse Asus's solution and test the performance that an early version of the SATA Express interface is able to provide.

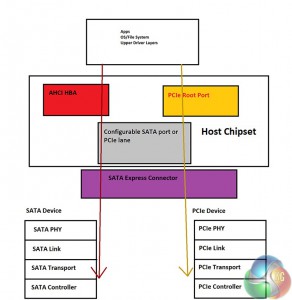

So, what is SATA Express? Taken from SATA-IO's FAQ regarding the specification, “SATA Express is a section within the new SATA v3.2 specification which defines host and device connectors that support SATA or PCIe. SATA Express provides an ecosystem for client storage in which SATA and PCIe solutions can coexist. PCIe technology enables up to 1GB/s per lane, as compared to SATA at 0.6GB/s. SATA Express includes support for up to two PCIe lanes, or up to 2GB/s.”

SATA Express allows devices to maintain compatibility with existing SATA applications but also make use of the PCIe interface for increased bandwidth and reduced latency. According to SATA-IO, the use of PCIe lanes will allow SATA Express interface speeds of 8Gbps (two lanes of PCIe 2.0, minus overhead) and 16Gbps (two lanes of PCIe 3.0) to become common implementations.

The SATA Express specification states that devices must be able to support both SATA and PCIe. As shown in the block diagram above, data has two ways of flowing through the system; the PCIe route or the SATA route. The route taken will depend upon the attached device. Backwards compatibility is enforced by the SATA route.

In regard to the motherboard-based SATA Express connector, customers can choose the connection type that suits their requirements; SATA Express via PCIe for increased bandwidth from a supported device, and the current-generation SATA connection for presently-available storage drives.

Why not just double the SATA bandwidth, as has been done in previous generations? According to SATA-IO, a 12Gbps SATA interface would be more power hungry than using PCIe lanes and it would take longer to implement than SATA Express. A shorter time-to-market and suggested power savings paved the way for SATA Express.

Utilising the PCIe interface, SATA Express can be set to use up to two PCIe 2.0 or PCIe 3.0 lanes. Minus the encoding overheads, SATA 6Gbps provides a transfer speed of 0.6GB/s (approximately 600MB/s). Compare this to PCIe 2.0 which provides 0.5GB/s (after overheads) per lane and there is already feasibility for an easily obtainable 400MB/s (67%) speed increase using a two-lane SATA Express implementation.

Now focus on PCIe 3.0, which uses the more efficient 128b/130b encoding scheme, and 1GB/s of data can be crammed through a single lane, resulting in a 1.4GB/s (233%) speed increase over SATA 6Gbps for a two-lane SATA Express solution.

The numbers speak for themselves; in one fell swoop, SATA Express has the potential to remove many of the current bottlenecks that SATA 6Gbps is enforcing, allowing storage devices to once again be challenged by an interface's throughput potential.

Physically, the SATA Express Host plug is essentially a pair of SATA connectors fixed next to a connection carrying additional PCIe lanes. Much of the PCIe connection is fed through the SATA cables, but the extra connector is required to provide two full PCIe lanes.

My first impressions of the connector are that it is cumbersome. Perhaps this is a little harsh given the throughput increase and requirement for backwards compatibility, but it's similar to what we saw when moving between the USB 2.0 and USB 3.0 headers – a substantial size increase.

How exactly the SATA Express plug will change over time is unclear. Asus's technical material does state that the SATA Express cable may be subject to change at a later date.

We have spoken about SATA Express in general, but how exactly does Asus implement the connection on its Z87 Deluxe motherboard? After all, this could well be the makeshift solution that will serve on motherboards until Intel (or AMD for that matter) incorporates SATA Express onto its chipsets.

For Asus's solution, one of the SATA Express connections is linked to the Z87 chipset. Two PCIe 2.0 lanes are directed from the PCH to the relevant SATA Express connector (along with the relevant SATA 6Gbps connections for backwards compatibility).

The other SATA Express connection is provided by an ASMedia ASM106SE controller. Asus told us that the ASMedia controller hasn't been officially launched yet, hence why information regarding the IC is particularly scarce. The company also pointed out that its adoption may be subject to change.

Using two PCIe 2.0 lanes, Asus's SATA Express solutions are capable of up to 1GB/s transfer speeds (after removing overheads).

It is feasible for PCIe 3.0 lanes to be re-directed from the CPU to a SATA Express connection, allowing for transfer speeds of up to 2GB/s. This solution seems somewhat less likely on mainstream platforms due to the limited number of PCIe 3.0 lanes, but it could be viable for Intel's HEDT platform.

Firstly let's address the problem with testing SATA Express. The main issue would be the lack of commercially available drives which support the high-speed PCIe version of the interface.

To overcome this problem, Asus uses a custom-built board which connects to the motherboard via SATA Express. Attached to this board (called Runway) is a physical PCIe slot which allows a PCIe device to be connected.

The result is a connection which is operated via the SATA Express interface and uses a drive which is fast enough to test the implementation's speed.

An external clock cable is used for the PCIe clock signal, although Asus indicates that this isn't necessarily going to be required in the future when connecting a native SATA Express device which uses the PCIe connection.

In order to test the speed of SATA Express, Asus uses its PCIe ROG RAIDR Express SSD. The RAIDR is effectively a pair of RAID-0 SandForce SF2281 SSDs together on a single board. Sequential read and write speeds for the RAIDR are stated as 830MB/s and 810MB/s, respectively.

Numbers in the 800MB/s range are what make the RAIDR an excellent choice for testing the bandwidth provided by Asus's SATA Express implementation.

We hooked up the necessary cables and tested the SATA Express connection using the ROG RAIDR and Asus's Runway board. Our test system's Windows 7 64-bit OS was installed on a Samsung 840 SSD.

Test System:

- Processor: Intel Core i7 4770K Retail @ stock.

- Motherboard: Asus Z87 Deluxe SATA Express.

- Memory: 8GB (2x 4GB) G.Skill RipjawsX (F3-2133C9Q-16GXL) 2133MHz 9-11-11-31.

- System Drive: 500GB Samsung 840 Series SSD.

- Operating System: Windows 7 Professional with SP1 64-bit.

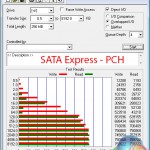

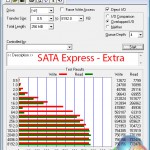

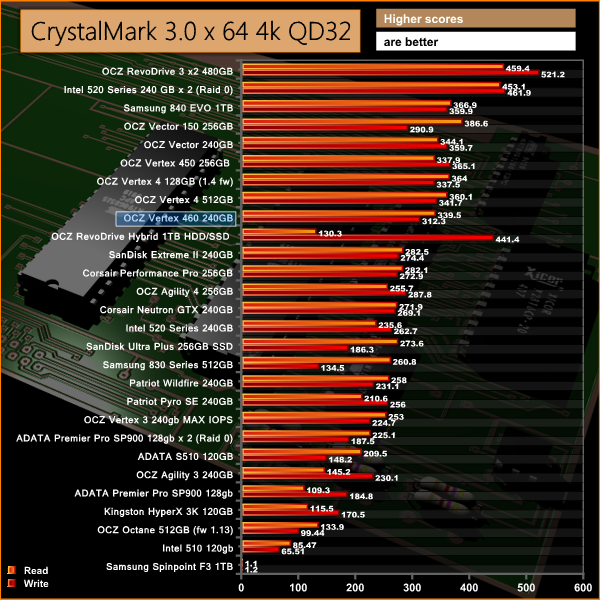

We tested both SATA Express connectors; one implemented via PCIe 2.0 lanes directly from the Intel PCH and the other operating via an ASMedia ASM106SE controller. We will also include numbers for the ROG RAIDR operating directly from a native PCIe slot. An SF2281-equipped SanDisk Extreme 120GB serves as the SATA 6Gbps comparison.

Asus made it clear to us that this is a technology demo board – it is not a final product and still has some known (and presumably many unknown) bugs. As such, the numbers presented from our testing should be interpreted with caution.

Our article aims to provide an early insight into the type of performance that we can expect from the SATA Express interface.

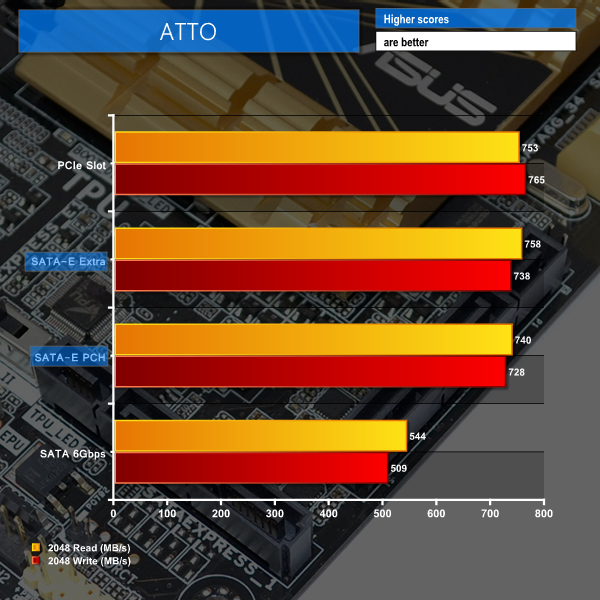

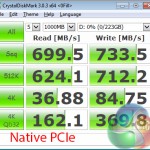

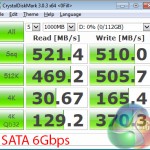

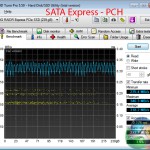

Sequential read and write results from ATTO are well over the 700MB/s mark for both SATA Express implementations. Connected via native PCIe, the ROG RAIDR does seem to offer a marginal increase in performance, but as we have already pointed out, this is likely due to the SATA-E connector still undergoing finalisation.

Compared to a fast SSD capable of nearing the SATA 6Gbps interface's saturation point, SATA Express offers an average throughput increase of more than 39%. In comparison to the slightly higher-scoring external (ASMedia-fed) SATA Express interface, the average throughput increase over our test drive using SATA 6Gbps is 42%.

CrystalDiskMark's highly compressible data test (0x00, 0Fill) sees the RAIDR delivering around 700MB/s sequential read when connected via both SATA Express interfaces and the native PCIe slot. As we observed with Atto, native PCIe does seem to have a slight performance advantage, but this could be related to the relative immaturity of Asus's SATA Express implementation.

An increase in performance of over 30% can be obtained by switching from the saturated SATA 6Gbps interface to the SATA Express successor and a fast drive.

Quite clearly, SATA Express is currently limited by the speed of the drive that is connected. We haven't been able to say this about a storage subsystem in a while, but it actually looks like the connection interface can provide an excess of bandwidth (for current consumer SSDs, at least).

Worth pointing out is the discrepancy between 4K write results for the SATA Express interfaces compared to the native PCIe connection. After numerous reattempts with different driver, power, software, and connection combinations, we contacted Asus who looked into the issue and suggested that it is simply a bug related to the early SATA Express implementation. Given the relatively tight grouping of results that we have recorded throughout testing, we see no reason to disagree with Asus's suggestion.

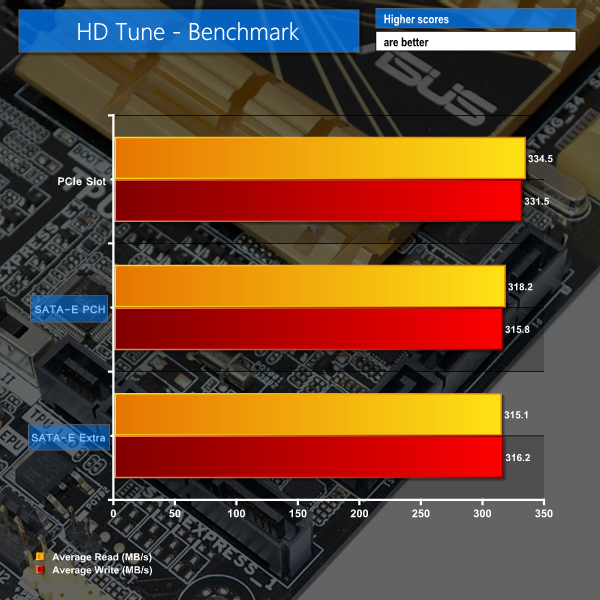

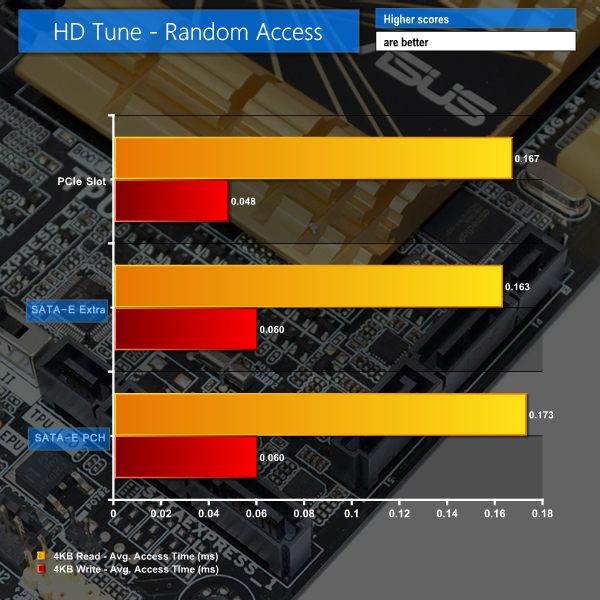

HD Tune's read and write benchmarks show SATA Express managing to keep within a close margin of PCIe's performance figures.

As a result of the similar average transfer speeds, access time results were also closely matched between the three different connections.

Average access time for the 4kB random read test showed similar performance for each interface. A maximum recorded difference of around 6% is no cause for concern when taking the precision of HD Tune's test into account.

Average access time for the 4kB random write showed clear preference towards the RAIDR being used on a native PCIe connection. This mirrors the 4K write results presented by CrystalDiskMark. Compared to direct PCIe, increased latency for SATA Express could be understood; the data has to pass through additional controllers and/or the Z87 chipset.

But given that this is a technology demo board and SATA Express is still undergoing development and finalisation, it would be fair to guesstimate that the discrepancy is related to another early-release bug. We would be surprised if bugs such as this were still present upon official release of a retail product.

So there we have it; SATA Express looks to be the solution that can re-ignite the flame of innovation for SSD vendors. Asus has proven that a two-lane, 1GB/s storage connection is viable for use with current PCIe 2.0-equipped platforms. And there's no reason to rule out PCIe 3.0 implementations which provide 2GB/s of bandwidth.

There's no denying that SATA Express isn't perfect. Although still being finalised, the connector is bulky and cumbersome. Connections are limited to two PCIe lanes which, even when using Gen 3 connections, look to already be a limiting factor in the very near future, as proven by SandForce SF3700-equipped devices.

But what SATA Express does well is offer a solution which, quite frankly, destroys SATA 6Gbps in terms of bandwidth. And it's the interface's relatively simple design that will allow it to enter the market rapidly, unlike it is suggested the theoretical SATA 12Gbps would have.

Backwards compatibility is nice, but for the enthusiast consumer, SATA Express looks to be the long-awaited worthy solution for high-speed storage devices. PCIe devices have gained popularity in the high-speed storage segment, but many products have a number of shortfalls – taking up a motherboard slot and hit-or-miss compatibility with technologies such as TRIM (although this has been all but wiped out), to name just a few.

With SATA Express, enthusiasts aren't limiting their graphics options by using up valuable PCIe slots; the storage devices can be housed in a standard chassis bay, leaving ample room for multi-GPU configurations. And drive vendors are less limited in terms of physical dimensions; there's no reason why a thick 2.5″ or 3.5″, multi-PCB SATA Express SSD can't be provided for desktop enthusiasts.

Perhaps the biggest question regarding SATA Express is one that has yet to be answered. How will it fair in regard to adoption? Hopefully Intel will select express delivery for SATA-E, although whether or not that will be the case is still unclear. Early information suggested the SATA Express would feature on the 9-series chipset, but more recent reports suggest that the semiconductor giant will not be providing SATA Express on its upcoming chipset, opting instead for the PCIe-fed M.2 form factor.

As already mentioned, SATA Express adoption in the near future could be at the discretion of motherboard vendors, unless Intel adds native support to its upcoming chipset. And then there's the question mark surrounding widespread adoption from SSD vendors. Regarding SSD vendors, there could be some hope for SATA Express devices in the near future; we contacted ADATA who confirmed that they would be releasing SATA Express drives as soon as the controllers are ready.

M.2 could act as a barrier on the road of SATA Express adoption. Information suggests that, on the 9-series chipset, the SFF interface will use two PCIe 2.0 lanes to provide 1GB/s transfer speeds. That's the same as current (and soon to come, possibly) iterations of SATA Express. Both SATA-E and M.2 will offer support for the NVMe specification, too. And M.2 devices have already started trickling onto the market.

Despite the hurdles, SATA Express still has its place on the computing scene. Only so much NAND can be physically squeezed onto an M.2 device, after all, and high density chips are not priced linearly proportional to their capacity increase. And with the use of PCIe 3.0 lanes, SATA Express could offer double the bandwidth of suggested M.2 implementations. High-speed external drives could also make use of the SATA Express interface, especially those equipped with Thunderbolt or the upcoming USB 3.1 connector.

It's refreshing to see a motherboard vendor such as Asus taking a bold step and offering support for an upcoming interface. Yes, this is only a technology demo board, but it shows that the company has the future of storage in its thoughts.

To conclude, SATA Express looks to be the next logical step for desktop storage devices. M.2 will look after the SFF and mobile scenes, but when it comes outright speed and high capacities on the desktop side of the consumer market, SATA Express should have us covered.

You can discuss this article on our Facebook page, over HERE.

KitGuru KitGuru.net – Tech News | Hardware News | Hardware Reviews | IOS | Mobile | Gaming | Graphics Cards

KitGuru KitGuru.net – Tech News | Hardware News | Hardware Reviews | IOS | Mobile | Gaming | Graphics Cards

Great read there, looking forward to the next generation boards.

just devote a pcie slot to storage and just have pcie style SSD/HDD

I hope the new range of motherboards have this technology available, its a great idea. I use a lot of drives in RAID to get the max speed.

When are these going to be available?

That asus card takes up a lot of space, would be an issue with a system containing multiple GPU’s. the board looks great though, id be interesting in selling my current asus board and getting a new one this year if this gets adopted.

Fascinating read, spent the last hour on this article. thanks Kitguru.

The only issue will be the cost of adoption this year, the ASUS card is quite expensive still, although I see Amazon should have stock in soon.

I did enjoy the read, learned a few things as well, which is always good.